Ridiculing and questioning Islam, Muhammad, the Qur'an and religion in general is an ancient tradition in Muslim countries.

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/khaled_diab/2007/06/the_muslim_faithless.html

Saturday 30 June 2007

Monday 25 June 2007

Neither here nor Blair!

By Khaled Diab

After he hands over the reins of the premiership to Gordon Brown, Tony Blair intends to become a Catholic and is prime candidatefor the job of Middle East peace envoy for the largely dormant Quartet (USA, EU, UN and Russia).This is a proposal that is hardly set to get the pulse racing at the exciting possibilities that, through the good offices of Blair, Israelis and Palestinians will move infinitely closer to peace. Given his own personal track record on Middle Eastern peace - namely invading Iraq and turning it into an anarchistic battleground and garnering a reputation in the Arab world as a 'war criminal' - his candidacy can only baffle and bewilder, not inspire. If you though Paul Wolfowitz at the World Bank was bad - think again!

One can just imagine him addressing Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and his team in a closed session, earnestly pressing his sweaty palms together as he earnestly urges them in a voice of feigned earnestness, to give peace a chance. "You chaps really ought to stop bombing Gaza."

"Well, you bombed Iraq," the Israelis would remind him.

"Well, that was different," he would protest. "We were liberating the Iraqis from that evil Saddam."

"Well, the Palestinians can hit us in much less than 45 minutes - and we don't need a sexed up dossier to claim that." "Well, how about you end the occupation of the West Bank?" "Well, how about you end the occupation of Iraq?"

And then how would Blair handle the Palestinians, given the fact that he was one of the engineers of the international boycott that has brought such misery and destitution raining down on them. I mean, as prime minister, he's hardly shown much visionary potential as a peacemaker. If he had, he would've urged the USA and Israel to engage with the Palestinian unity government, rather than turn the screws and help percipitate the current chaos and lawlessness in Gaza.

What would've been better: a moderating Hamas engaging with the outside world or a hardening Hamas stamping de facto control over the streets of Gaza? I don't see how Tony Blair could broker with the Palestinians. Hamas would probably refuse to see him and any moderate Palestinian who did would be committing political suicide. So, at the end of the day, this ridiculous proposal seems to be neither here nor Blair - and the conflicts endless cycle will continue to spin.

Labels:

catholicism,

israel,

middle east envoy,

palestine,

quartet,

tony blair

Sunday 24 June 2007

The other right of return

Palestinians have not been the Middle East's only victims. We Arabs should recall the many Jews who paid the price for the Arab-Israeli conflict.

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/khaled_diab/2007/06/the_other_right_of_return.html

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/khaled_diab/2007/06/the_other_right_of_return.html

Tuesday 19 June 2007

The Middle Eastenders

Khaled Diab

This weekend I went to London for a mini trip to the Middle East for an encounter with Jewish, Israeli and Palestinian (not to mention Sikh!) intellectuals, as well as a reunion with old friends from Egypt.

After a massive delay on the Eurostar owing to a broken rail in one of the tunnels, I arrived in Hackney at around midnight. Hatem, one of my oldest and dearest friends, and I stayed up late into the night shooting the breeze, despite the fact he had to get up early to go to work, even though it was the weekend. We caught up on everything that had happened in the nine months or so since we’d last met, swerving and veering and flowing with the conversation – with Hatem puncturing the late-night silence with his rapid-fire fire and brimstone-style impassioned delivery. When he speaks, he can make an offer of coffee sound like a revelation.

The next morning we all got off to a late start, delayed by conversational congestion. We heard on the TV in the background that Salman Rushdie had been made a knight – and it disappointed me to learn that he’d accepted it. Why is it ageing radical rockers and novelists seem to go gooey at the knees in middle-age and allow the establishment they once pilloried to claim them as its own?

To my mind, the author of such daring and creative post-colonial literature as Midnight’s children, The Moor’s last sigh and The satanic verses, which mock, deride and sympathise with history’s human products and progenerators. For someone who was born, like the characters in Midnight’s children, the year of India’s independence, I would’ve expected him to turn down that ultimate symbol of empire and refuse to become a ‘knight of the realm’, particularly given how mocking he is of England.

But, then again, he has increasingly become an establishment figure in recent years, with his cheerleading of the American policy, etc. Despite his obvious talent and rebelliousness, elements of haughtiness and vanity bedevil his persona and his works. I also think his own condition must prey on him and this is reflected in the fact that the antiheros of his novels always seem to have fetched up in some degenerate cul-de-sac of the soul. Sir Salman, you’ve lost your edge.

As we discussed whether or not he should’ve worshipped the ground beneath the Queen’s feet, we thought London had been transformed into Baghdad as fighter jets flew overhead. Luckily, it was only the Red Arrows engaging in their acrobatic amaze and awe, rather than the Royal Air Force’s bloodier version, shock and awe.

Finding a break in the clouds and avoiding the pomp and ceremony around the palace, we headed for SOAS, where Manuela, Hatem’s girlfriend is doing an MA on Arab perceptions of their black minorities.

Would future immigrants have to attend trooping the colours ceremonies as part of their citizenship ceremony proposed by Ruth Kelly and Liam Byrne I wondered, as I overheard SOAS faculty lampooning the Kelly-Byrne package in the student bar. My interest in all issues multicultural meant that I could not hold my tongue and joined the fray in mocking the proposals.

Political encounters

Later, I met Brian Whitaker, The Guardian’s Middle East editor, in what has become something of a tradition whenever I’m in London. We went for a drink in Islington and talked about a Middle East angle for the ‘summer of love’, honour killings, the situation in Gaza and how the future might pan out.

In the evening, I went to dinner at Linda Grant’s place in north London. The novelist and writer had started up a correspondence with me during my trip to Israel and Palestine and I had been invited for one of her Middle Eastern ‘diwans’.

To get to her house, I had to go via Finsbury park, the famous one-time home of Abu Hamza al-Masri, or ‘Captain Hook’, as the tabloids colourfully call him. With some time to kill, I stopped off for a cappuccino at an espresso bar which turned out to be run by Algerians. When I remarked that they were a long way from the normal Algerian destinations, they told me that everyone was looking for a way out of that den of extremism.

When they counted zena (adultery, i.e. pre-marital and extra-marital sex) as one of the issues bringing down the country. I was flabbergasted that he could put sex on a par with political and financial corruption, nepotism, extremism and violence. “What’s sex got to do with it?” I asked.

“Well, they’re enraging God,” he replied matter-of-factly.

“Let’s leave religion aside for a second.”

“No, we can’t do that!” he said, slightly offended.

“Please, just for the sake of argument.”

“Okay.”

“When a young couple go off and make love to each other, who are they hurting?”

“It’s haram. They might have an illegitimate child – they’ll be hurting that child.”

“But they’re not hurting society. If they are hurting anyone, they are only hurting themselves, whereas a corrupt politician or a violent Islamist is hurting everyone.” He conceded that I had a point. Depressed by the state of sexual liberty in people’s minds, I cheered myself up by with the thought that I’d dropped a small sex bomb into their cosy bigotry. Ahh, when the sexual revolution comes, they’ll realise that making love makes the world a better place.

Linda had invited Palestinian writer Samir el-Youssef, Israeli photojournalist Judah Passow and Sikh journalist Sunny Hundal. However, Judah was stuck in Amsterdam airport and so was unable to make it.

The conversation also went to Gaza and what could be done there. Samir also recalled his spectacular debate with a Hamas politician at the Hay festival in which he professed his atheism. I noted my view that agnosticism was the most rational choice, since no one could prove conclusively either way whether or not a god existed. This sparked a lot of controversy and a long debate on comparative religion. Sunny provided us who came from the Abrahamic tradition with a lot of interesting insights into Sikhism, Hinduism and Buddhism.

After much food for thought, it was off, with Hatem and Manuela, to a Moroccan restaurant in Covent Garden for the birthday party of an old friend from the Cairo days, Jessica. Sunday was spent in true Middle Eastender style, kicking back and wondering around the markets of the Eastend and strolling along the Embankment.

After a massive delay on the Eurostar owing to a broken rail in one of the tunnels, I arrived in Hackney at around midnight. Hatem, one of my oldest and dearest friends, and I stayed up late into the night shooting the breeze, despite the fact he had to get up early to go to work, even though it was the weekend. We caught up on everything that had happened in the nine months or so since we’d last met, swerving and veering and flowing with the conversation – with Hatem puncturing the late-night silence with his rapid-fire fire and brimstone-style impassioned delivery. When he speaks, he can make an offer of coffee sound like a revelation.

The next morning we all got off to a late start, delayed by conversational congestion. We heard on the TV in the background that Salman Rushdie had been made a knight – and it disappointed me to learn that he’d accepted it. Why is it ageing radical rockers and novelists seem to go gooey at the knees in middle-age and allow the establishment they once pilloried to claim them as its own?

To my mind, the author of such daring and creative post-colonial literature as Midnight’s children, The Moor’s last sigh and The satanic verses, which mock, deride and sympathise with history’s human products and progenerators. For someone who was born, like the characters in Midnight’s children, the year of India’s independence, I would’ve expected him to turn down that ultimate symbol of empire and refuse to become a ‘knight of the realm’, particularly given how mocking he is of England.

But, then again, he has increasingly become an establishment figure in recent years, with his cheerleading of the American policy, etc. Despite his obvious talent and rebelliousness, elements of haughtiness and vanity bedevil his persona and his works. I also think his own condition must prey on him and this is reflected in the fact that the antiheros of his novels always seem to have fetched up in some degenerate cul-de-sac of the soul. Sir Salman, you’ve lost your edge.

As we discussed whether or not he should’ve worshipped the ground beneath the Queen’s feet, we thought London had been transformed into Baghdad as fighter jets flew overhead. Luckily, it was only the Red Arrows engaging in their acrobatic amaze and awe, rather than the Royal Air Force’s bloodier version, shock and awe.

Finding a break in the clouds and avoiding the pomp and ceremony around the palace, we headed for SOAS, where Manuela, Hatem’s girlfriend is doing an MA on Arab perceptions of their black minorities.

Would future immigrants have to attend trooping the colours ceremonies as part of their citizenship ceremony proposed by Ruth Kelly and Liam Byrne I wondered, as I overheard SOAS faculty lampooning the Kelly-Byrne package in the student bar. My interest in all issues multicultural meant that I could not hold my tongue and joined the fray in mocking the proposals.

Political encounters

Later, I met Brian Whitaker, The Guardian’s Middle East editor, in what has become something of a tradition whenever I’m in London. We went for a drink in Islington and talked about a Middle East angle for the ‘summer of love’, honour killings, the situation in Gaza and how the future might pan out.

In the evening, I went to dinner at Linda Grant’s place in north London. The novelist and writer had started up a correspondence with me during my trip to Israel and Palestine and I had been invited for one of her Middle Eastern ‘diwans’.

To get to her house, I had to go via Finsbury park, the famous one-time home of Abu Hamza al-Masri, or ‘Captain Hook’, as the tabloids colourfully call him. With some time to kill, I stopped off for a cappuccino at an espresso bar which turned out to be run by Algerians. When I remarked that they were a long way from the normal Algerian destinations, they told me that everyone was looking for a way out of that den of extremism.

When they counted zena (adultery, i.e. pre-marital and extra-marital sex) as one of the issues bringing down the country. I was flabbergasted that he could put sex on a par with political and financial corruption, nepotism, extremism and violence. “What’s sex got to do with it?” I asked.

“Well, they’re enraging God,” he replied matter-of-factly.

“Let’s leave religion aside for a second.”

“No, we can’t do that!” he said, slightly offended.

“Please, just for the sake of argument.”

“Okay.”

“When a young couple go off and make love to each other, who are they hurting?”

“It’s haram. They might have an illegitimate child – they’ll be hurting that child.”

“But they’re not hurting society. If they are hurting anyone, they are only hurting themselves, whereas a corrupt politician or a violent Islamist is hurting everyone.” He conceded that I had a point. Depressed by the state of sexual liberty in people’s minds, I cheered myself up by with the thought that I’d dropped a small sex bomb into their cosy bigotry. Ahh, when the sexual revolution comes, they’ll realise that making love makes the world a better place.

Linda had invited Palestinian writer Samir el-Youssef, Israeli photojournalist Judah Passow and Sikh journalist Sunny Hundal. However, Judah was stuck in Amsterdam airport and so was unable to make it.

The conversation also went to Gaza and what could be done there. Samir also recalled his spectacular debate with a Hamas politician at the Hay festival in which he professed his atheism. I noted my view that agnosticism was the most rational choice, since no one could prove conclusively either way whether or not a god existed. This sparked a lot of controversy and a long debate on comparative religion. Sunny provided us who came from the Abrahamic tradition with a lot of interesting insights into Sikhism, Hinduism and Buddhism.

After much food for thought, it was off, with Hatem and Manuela, to a Moroccan restaurant in Covent Garden for the birthday party of an old friend from the Cairo days, Jessica. Sunday was spent in true Middle Eastender style, kicking back and wondering around the markets of the Eastend and strolling along the Embankment.

©Khaled Diab. Text and images.

Sunday 10 June 2007

2048: a hundred years of interludes

By Khaled Diab

This month, there has been a general preoccupation with the 1967 war and the occupation that started 40 years ago. But all the retrospectives have done little to raise people's optimism that peace is attainable. It might now be worthwhile to cast our sights four decades into the future and consider Israel's first centennial.

In 2048, will it depressingly be 'business as usual' - only even more entrenched than it is today, with the land carved up into severed, separated and heavily armed Israeli and Palestinian bantustans and ghettoes? Will it possibly have turned 'apocalyptic', with the region-wide war many have been fearing finally engulfing the Middle East, spreading out from the two epicentres of Iraq and Iran, and Israel and Palestine, to subsume everything in between and a lot that lies beyond?

I'm going to be optimistic and dream of desirable and remote, yet plausible, future.

____________________

Israel celebrates first centennial

Staff and agencies

Israelis took to the streets today in jubilation to mark the hundredth anniversary of the painful birth of their once troubled nation. In Palestine, Palestinians, who also today celebrate 15 years of independent nationhood and the fulfillment of their national aspirations, extended warm congratulations to their Jewish neighbours.The legendary one-time Israeli and Palestinian premiers, after attending separate Independence Day rallies in their respective capitals, Tel Aviv and Ramallah, came together in jointly adiministered Jerusalem, the two nations' spiritual capital, for a joint celebration with thousands of revellers.

"Words cannot express my pride and joy on this special day," a clearly emotional Shalom V___, the charismatic one-time Israeli prime minister, told the assembled crowd as he fought back the tears. "I am proud to be alive at this important moment in the Jewish people's history. After two millennia of statelessness, the Jewish people's dream of nationhood has gone from strength to strength over the past century. Today, we can truly hold our heads up high as proud members of the family of nations, now that we and the Palestinians have found a way of living together in peace and prosperity. I would like to take this opportunity to wish our brothers and sisters in Palestine a happy 15th birthday for their nation."

A deafening roar gripped the mixed audience of Israelis and Palestinians who spontaneously began to chant the name of Salama B____, the popular ex-Palestinian prime minister. "Just 20 years ago, the idea that a Palestinian leader could be standing here wishing Israel a happy birthday was still unthinkable. We've come a long way. It has not been easy for my people to come to terms with the painful reality that accompanied the loss of our land in 1948, but our Jewish brothers and sisters also suffered a lot in their exile. Now they are safe among their brethren. From the very bottom of my heart, I wish Israel many centuries more of prosperous coexistence."

The still youthful-looking Salama and Shalom, who prefer to stress the peaceful connotations of their first names, hugged like the two veteran comrades they were.

The path to peace

Back in 2007, while the world was marking the 40th anniversary of the 1967 war, Salama was into his fifth year in administrative detention in an Israeli prison. As a passionate young idealist, the pictures of Ariel Sharon entering the Al Aqsa Mosque complex with hundreds of troops had led him, the introverted medical doctor, to join the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade. He was engaged in a number of gunbattles with the better-armed IDF soldiers, but was opposed to suicide bombings and attacking civilians. This set him on a collision course with the more extreme factions of the group, but the imminent standoff was averted by his capture and arrest during another shoot out with the Israeli army, ironically while tending to the soldier he'd critically wounded.

As he was a fairly senior member of the Brigade, the Israeli officer in charge of Salama did not symapthise with Salama's distinction that, in a war, it was legitimate to attack soldiers - besides he did not believe that Salama had no part to play in any attacks against civilians. "Even if what you say is true, you're my POW until the end of this war," the hawkish officer famously said.

Little did this officer suspect that he was aiding the prospects for peace. In prison, Salama learnt to speak fluent Hebrew and discovered a passion for history - and what he learnt about Jewish history did not quell the anger in his breast that he felt at the plight of his people, but it caused him to feel compassion for the other side. He also started up a correspondence with a junior Knesset member and historian, Shalom. Together, they realised the powerful explosive effect of history and ideology and so set about to defuse it. Slowly, they formulated a common history which gave credence to both sides. It sought to replace the current epic narratives of both sides, with more nuanced narratives, with some epic elements.

Although the Jews had seen conversion and intermixing in the two millennia since they were exiled by the Romans and the indigenous population that was left had seen a fair bit of immigration and converted to Christianity and Islam, the two young men came up with the appealing storyline of long lost brothers and sisters coming home to their family after years of suffering and pain. However, the ensuing family feud had made the reunion an ugly one, but now it was time to drop the familial bickering and work together for their common good.

They also agreed to work together on 'bread and butter' issues. Shalom, then only 31 and with no military background, began a clever and charismatic grassroots campaign calling for Salama's release. Once out of prison in 2009, Salama faced some suspicion of being a 'collaborator', but his natural intelligence and charm and his simple message of 'individual dignity before national pride' won him many converts among the hard-pressed Palestinian population, at a time of Israeli closures and crushing occupation, international embargo, civil war in Gaza and the West Bank, and regular bloody skirmishes with the Israeli army. And the many scattered groups involved in non-violent activism found in him and Shalom natural leaders.

Timeline to independence

Together, Salama and Shalom effectively turned the Palestinian struggle into a civil rights movement for the next decade or so. By around 2018, the movement they'd spawned turned its attention to Palestinian autonomy, which was achieved in 2021. The vexed issue of refugees was handled through a sustainable number of Palestinians being allowed to return each year, compensation for those willing to stay away - and the entire Palestinian diaspora being allowed to visit. The Arab countries which had had significant Jewish populations also instigated a right of return for those Middle Eastern Jews who had been made refugees after the creation of Israel and their offspring wishing to return to their ancestral homelands and revive the once vibrant Jewish minorities there. Most who returned came from Europe or the USA, but some also moved from Israel.

After a dozen years of autonomy, rapid economic growth and convergence between Israel and Palestine, the time came to decide on the fate of the two nations. In 2033, two separate referendums were held among the two peoples outlining the options ahead. Surprisingly for some observers, a majority of Palestinians and Israelis voted for the creation of an independent Palestinian state, but then for its immediate entry into a federal union with Israel. The Palestinian state was born on the same day as the Israeli one 85 years previously, so that the day of Israel's joy - traditionally associated with Palestinian tragedy and despair - would also be that of Palestine's, set according to the lunar calendar common to Judaism and Islam. In addition, Israeli remembrance day was broadened to include the Palestinian 'naksa'.

'Given the size of this land and the proximity of our two peoples, that is the only sensible option," Shalom said at the time.

"In the past, we had our hands at each others' throats. Today, our two peoples have voted to walk into the future hand-in-hand," said Salama, independent Palestine's first premier.

Labels:

2048,

israel,

israel's centennial,

palestine,

palestinian independence

Friday 8 June 2007

Testing times

Across Europe, the real challenge when dealing with minority groups is not integration but marginalisation.

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/khaled_diab/2007/06/testing_times.html

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/khaled_diab/2007/06/testing_times.html

Tuesday 5 June 2007

Of bombs and bombast

By Khaled Diab

While the west was discovering new self-confidence and freedom as it basked in its ‘Summer of Love’, the Arab world was waking up to the winter of its humiliation.

Although the eight-year-old Vietnam war was preying on the conscience of western youth, it didn’t spoil the baby boomer party back home. June 1967 saw the world’s first major rock festival, the Monterey Pop Festival. The Beatles released their groundbreaking album Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club on 1 June 1967.

Less than a week later, Israel attacked its Arab neighbours. It is said that God made the heavens and the earth in six days and on the seventh he rested. In six days, Israel brought the heavens crashing down around the Arabs’ ears and, on the seventh day, the Arabs were left to sweep away the debris of their shattered pan-Arabist dreams.

It will remain a bone of contention why Israel started that conflict. Israel claims the war was a ‘pre-emptive’ strike. Although the Israeli public were terrified and felt that Israel’s imminent destruction might be at hand, the military’s hawkish top brass had a different idea. The country’s dovish prime minister Levi Eshkol did not want a military confrontation with the Arabs and tried to beat back the warmongers, but the hawks proved tougher than the doves and flew Moshe Dayan in as defence minister to guarantee a standoff.

Then IDF chief of staff Yitzhak Rabin, who had not yet been reborn as a dove and was still a hot-headed militarist escalating the confrontation with Syria and threatening to invade it, later admitted that: “Nasser did not want war.”

Even the conservative and Israel-leaning The Economist concluded in its 26 May 2007 issue: “It was a war prompted by a gung-ho [Israeli] military, a misreading of the enemy’s intentions and political expediency”.

It seems that the Israel’s military leaders were convinced that they had to crush the Arabs while Israel still enjoyed massive military supremacy and that any delays could result in a protracted conflict further down the road. In addition, if the war was not about land, resources and ‘strategic depth’ as it later became known as, why are the Israelis still holding on to most of the prime real state they captured four decades ago? If they were only interested in forestalling an Arab attack, why didn’t they pull out once they’d so comprehensively crushed the Arabs?

The catastrophic price of bluster

But the Arabs have their own difficult questions to confront. If Nasser did not want war – as the sorry state of Egypt’s economy and military at the time, as well as government documents and private memoirs reveal – why did he feel compelled in such dangerous and risky brinkmanship?

Israel had bombs to back up the swagger of its generals; Egypt was armed only with bombast. If wars were won and lost on oratory, then Egypt would’ve been a superpower under Nasser.

“Because there was enough information available to Arab governments and the PLO which should have told them that they were not ready to do battle with Israel, it resembled an act of mass suicide,” writes Said Aburish, in his incisive biography of Nasser.

Aburish blames Nasser’s flawed and awful decisions on the ‘Arab street’ which this people’s dictator listened to very closely, and the longing of ordinary Arabs to go to war with Israel and win back some lost pride.

But the malaise ran far deeper. Nasser was Egypt’s first native son to lead her in 2,300 years, who hailed from a small, unprepossessing town in upper Egypt and was raised in Alexandria. He looked and spoke like an ordinary Egyptian, albeit more eloquently. Most importantly, he held out the promise to restore Egyptian – and later Arab – pride.

But that promise was not rooted in any reality or realistic road map; it was an illusion, even a delusion, which the Egyptian and Arab public lapped up gratefully and Nasser and his crew administered liberally. For the first few days of the war, the radio was full of dispatches from the ‘front’ claiming one improbable victory after another.

Ahmed Fouad Negm, who after the defeat would become Egypt’s leading ‘street poet’ and made colloquial Egyptian an acceptable language of poetry, bought into the illusion and was completely thrown asunder by the comprehensive defeat. He penned a biting satire which Sheikh Yassin, his future duet partner, put to music and sang.

Oh people of Egypt guarded by thieves

Cheap food is plenty and everything is okay

Thanks to people who sing to fill their stomach

Sing poems that glorify and appease even traitors

While Abdel-Jabbar is destroying the country

But the Arabs awoke from their collective delusion, the secular pan-Arab dream was dealt its final death blow. Long gone were the heady days of optimism of the 1950s; to a collective sigh of relief in western capitals where Nasser was seen as a bogey man, despite his early pro-western inclinations, because they failed to understand that ‘non-aligned’ did not mean ‘enemy’. Besides, the novelty of a ‘third world’ leader talking back and demanding to be treated as an equal was not something they appreciated. But with secularism slayed, Islamism rushed to fill the void.

The only silver lining for Arabs is that they lost their bluster and now pursue a far more realistic foreign policy. In fact, in the long term, it is Israel that is proving the victim of her own success, falling prey to the arrogance of the victor, it is unwilling to make the compromises needed to reach peace and ensure the country’s long-term sustainability.

©Khaled Diab

Saturday 2 June 2007

Streets apart: two women’s view of people, not politics

By Khaled Diab

Two books I read back to back do something that few books about the Israel-Palestinian conflict achieve: they look at the ordinary people, with the politics serving as mere backdrop to their human stories.

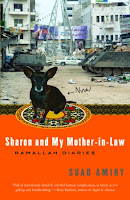

Since my tour of Israel and Palestine was all about humanising the conflict, I think it would be approporiate to meet the Palestinians and Israelis Suad Amiry and Linda Grant encounter in their highly readable and compassionate books: Sharon and my mother-in-law and The people on the streets: a writers’ view of Israel.

The first of the two books I read was Amiry’s – whom I had planned to meet while in Ramallah, but unfortunately she was delayed in Amman – which contains her regular correspondences from her house arrest in reoccupied Ramallah during Ariel Sharon’s famous offensive in 2002. The version I read also collected together this Palestinian architect’s diaries from the past quarter of a century and chronicles her move from Amman to Ramallah, including the epic journey to get official residency there, her PhD; her first-ever visit to Jaffa, her ancestral home; juicy gossip from the Ramallah grapevine; not to mention the cynicism, humour, compassion, resourcefulness and monotony of everyday life.

Linda Grant, a British Jewish novelist and journalist of a progressive persuasion, long ago came to the conclusion that there was not much she could do to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but decided that there was a human angle to it she was duty bound to highlight. And she does just that in her book, which mainly revolves around life in the colourful Ben Yehuda neighbourhood of Tel Aviv where she stays when she visits the country. But she also goes to Jerusalem and visits the Gaza settlements during the period of evacuation. She even recalls her first visit to Israeli as a starry-eyed teenager in 1967, just after the Six Day War; more interested in meeting boys than in politics and her anti-Zionism of the time being as much a teenage rebellion against her father as against the politics of the Israeli state.

Explaining her motivation for the book, she told me: “As I writer I can expend my energy on something which no writer should stand by and watch – the demonisation and dehumanisation of Israelis and Palestinians by each other and by their cheering sections abroad. That’s why I am such an admirer of your blog and your willingness to enter into dialogue.” In fact, I’ll be meeting up with her and some Palestinians and Israelis in London in a couple of weeks.

The human face of war

Between 29 March and 1 May 2002, there was a general curfew in Ramallah which was lifted for a few hours every few days to allow residents to run essential errands and restock their cupboards and fridges. Unfortunately for Amiry, her husband had been abroad on business and was stuck in Jerusalem for much of the duration, leaving her alone to rescue and live with her 92-year-old mother-in-law.

“Writing was an attempt to alleviate the tension caused and worsened by Sharon and my mother-in-law,” Amiry explains in the foreword.

Another unfortunate coincidence was that Amiry’s mother-in-law lived very near to Al Muqata’a, Arafat’s besieged and destroyed headquarters. The old lady’s electricity and water supply were cut off for all the days before her daughter-in-law could reach her.

After tremblingly coming face-to-face with Israeli tanks and military jeeps one time too many, Amiry decided to jump over the walls of people’s backyards in order to get to her mother-in-law’s house. “Those few hundred metres felt more like a few hundred kilometres,” she confesses.

Despite Amiry’s amateur heroics, her mother-in-law, Umm Salim, was not impressed when she opened the door: “Where, in God’s name, have you been?” she cried out, “I’ve been waiting for you for days.”

The distressed old woman flitted around her apartment fussing over what to pack. “Shall I pack my purple dress?” she asked concerned. Amiry, more concerned about how she was going to get the 92-year-old over all the walls, replied: “Just leave it. We’ll be back soon to pick everything up.”

“That’s what we said in 1948, too, when we left our house in Jaffa, and then it was also May,” recalled the worried old woman. When Amiry heard this, she stood still and began to cry.

A neighbour dissuaded her from trying to get the old woman over the walls. “You have to take the front door,” he told her. And, so, a terrified middle-aged woman and her aged mother-in-law stepped out into a war zone.

“You have to see these tanks,” Umm Salim. “Goodness me, look how big they are!” But the last thing Amiry wanted to do was to stop and admire the size of those killing machines.

Looking from the other side of the fence, Linda Grant visited and spoke to some soldiers. “I wanted to meet some soldiers, to find out what they thought and felt,” she writes. “because one thing I was sure of, they were not metal men, not terminators, manufactured in a Negev factory out of cyber-energised spare tank parts, but flesh and blood.”

She visited a mobile military unit charged with patrolling and guarding the West Bank. “… all around were these soldiers and all I could think of to say, on this first impression, was, ‘Kids! They’re just kids!”

“We peered inside the huts. I thought I was going to see bunks with neat rolls of olive-green bedding, anally retentive army tidiness, gleaming weapons. I was expecting order, and instead there was juvenile chaos.”

Every dog has its days

It took Amiry some seven years of toing and froing before she managed to get her permanent residency – and only after a dramatic confrontation with the city’s Israeli military chief. For her dog, it would prove to be an entirely different affair. “I didn’t know what would be harder: to end my boycott of Doctor Hisham [Ramallah’s only vet, who was sexist and bigoted] or to go to an Israeli vet who probably would have something against Arabs, but not against dogs,” she writes.

In the end, she decided the Israeli would be the better bet and headed off to a nearby settlement. The friendly vet, Dr Tamar, vaccinated Nura and delivered Amiry with a surprise: she gave the dog a Jerusalem ‘passport’. while her mistress could only dream of the human version. “You know what, Nura,” Amiry told her dog. “With this document, you can go to Jerusalem, while I and my car need two different permits.”

But, with some lateral thinking, Amiry put it to good use when she pretended to be the dog's chauffer to get through a checkpoint to Jerusalem without a permit. "As you can see, she is from Jerusalem and it is impossible for her to drive herself," she told the bemused Israeli soldier, who patted the dog on the head and waved the car through.

"All you sometimes need is a sense of humour," Amiry reflected.

Amiry also recounts a memorable incident of non-violent resistance. In September 2002, her entire neighbourhood got up in the dead of night to bang on pots, pans, lampposts, pylons, bins and even water tanks on rooftops to protest their house arrest and annoy the Israeli soldiers who had reoccupied Ramallah. Looking around to observe the madhouse, Amiry noted: "Even if Sharon and his occupation forces never get this message, it was good group therapy."

The trappings of nationhood

Israel was partly built on the Jewish desire to avoid future persecution and the dream of the Jewish people to enjoy the ordinary trappings of nationhood. “The urgent need for a superhero, for a Jewish tough guy who could take on the bad men of Nazi Germany, was rooted inside my father and all of his generation,” Grant observes. She tells of how her father’s most vivid and bewildering memory of his first trip to Israel was that a Jewish soldier was guarding a Jewish prime minister.

In the 1950s, some observers began asking why it was that Jews had gone “like sheep to the slaughter” in World War II. “And many Jews took that question personally… and decided that the Jews’ best defence was going to be not only retaliating, but getting the retaliation in first, to be on the safe side and to make sure the enemy knew what was what,” Grant describes.

And many of the older Israelis she met had moved there for the reason of not wanting to be ‘guests’ in ‘someone else’s’ land. The Russian grandmother of one Israeli she met had decided that “she was never going to live at the beck and call, generosity and mercy of a goy ever again”.

The Palestinians share with Israelis a sense of embattlement and having been betrayed by the entire world. In fact, it surprised me just how many Israelis believe, despite the obvious advantage of their position and their government’s efficient PR machine, the international media is against them. Palestinians, of course, believe the opposite.

Palestinians also possess the earlier Jewish yearning for the ordinary trappings of nationhood – which the Israelis managed, ironically, to achieve but only by, so far, denying it to the Palestinians.

In her book, Amiry expresses the desire for the normal things most of us take for granted. “One of my dreams;” she writes modestly, “is that my husband can come and pick me up from the airport or the Allenby Bridge when I come back home from abroad.”

“I have always been envious of my parents, as well as my grandparents, who lived at a time when travelling between the beautiful cities of the Levant was not such a huge ordeal,” Amiry recounts.

Let's hope one day that kind of freedom and mobility can be enjoyed again in the region.

©Khaled Diab.

©Khaled Diab.

Friday 1 June 2007

Aswat gives voice to Palestinian lesbians

Being gay in most of the Middle East is tough, although the issue is coming out of the closet in several countries, including Lebanon and Egypt. In the case of Palestinian homosexuals, they not only have to deal with conservative traditions but also the politicising of sexuality in the context of attempts to construct false ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomies. Lesbians have traditionally been invisible in Arab society. In this article, Aswat staff explain their efforts to open the eyes of Palestinian society to their plight, the support they have received from Israelis and how sexuality is acting as a bridge between the two sides.

___________________

On 28 March 2007, Aswat (Voices) held the first conference of Palestinian lesbians in Haifa (Israel). On this day, Aswat celebrated five fruitful years of engaging in social change and raising awareness in the Palestinian community in Israel; and launched the publication of its first book in Arabic: Home and Exile in Queer Experience: a Collection of Articles about Lesbian and Homosexual Identity.

The conference was considered a great success, as many experienced a feeling of intoxicating joy and pride in the air. Many said Aswat provides them with a safe and beautiful space, some called Aswat a challenge, some even declared that Aswat is living the impossible and writing history. Among the participants were Palestinian, Israeli and international lesbians and homosexuals, funders, journalists, and gay and human rights activists.

Attempts to silence our voices

Two weeks before the conference, the Islamic Movement had issued a statement to the press denouncing the event and claiming that Aswat is “a fatal cancer” that is “corrupting the Palestinian society, that should be forbidden from spreading in Arab society and should be eliminated from the Arab culture” and demanded the immediate cancellation of the conference.

Although this appalling statement had caused much stress, Aswat decided to proceed with the conference and not to break under the Islamic Movement’s intimidation. Ironically, this negative publicity drew even more attention to the event: 250 people registered for the conference in advance and an additional 100 joined on the day.

A celebration of Aswat’s groundbreaking work

The conference was structured around two main panels. The first panel discussed homosexuality and lesbianism in the Arab community. Rauda Morcos – the general coordinator of Aswat – talked about the fact that most women in Arab society, and not only lesbians, live their sexual identities in secret. Aida Touma-Solaiman – the director of the Palestinian feminist organisation Women Against Violence – said that Aswat represents a challenge, because it questions society’s social engineering and patriarchal hierarchy. Yousef Abu Wardy – a well know Palestinian actor – talked about the role Aswat plays in the chain of freedom, and how important it is for the people who believe in freedom of expression to support and empower that chain. Ruti Gur – a Mizrakhi feminist and activist – expressed her excitement as she called Aswat “a dream that came true and that no one had allowed herself to dream”.

The second panel discussed the new Aswat book. In this panel, Raafat Hattab – a young Palestinian gay and representative of Alqaws (Rainbow), a Palestinian community project – talked about his experience as a gay man and quoted a poem by Nizar Qabbani when he said “revolution begins in the womb of sadness.”

Nabila Espanioli – the director of Altufula Centre for early childhood education and women’s issues – spoke about Aswat’s role in writing history and in breaking taboos. Dr Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian – a lecturer at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem – discussed the significance of Aswat’s book for the Arabic language; she defined the linguistic revolution Aswat has initiated as one of “naming the nameless”. Haya Shalom – a Mizrakhi lesbian feminist activist – spoke about Aswat’s role in shaping the process that will bring about social change in the Arab and Jewish societies.

In addition to the panelists, guests of honour attended the conference and spoke in solidarity with Aswat. These included Leslie Feinberg, a lesbian transgender and Jewish communist and the author of Stone Butch Blues.

Aswat gains visibility and strength

The conference was a great success for Aswat on many levels. It put Aswat on the map of political and social change. Indeed, as the event got significant media coverage in the Arab, Israeli and international press, the Palestinian community has become more familiar with Aswat and its mission. In addition, more and more people are referring to Aswat for information about the gay, bisexual and transgender community within Palestinian society; and more women who are questioning their sexuality are now approaching the organization to receive support.

The conference also has given Aswat the opportunity to test the will of local human rights and feminist organisations to stand by its side; to verify the strength of existing alliances and to consider the possibility of further co-operation with local NGOs.

More on homosexuality in the Middle East

More on women, feminism and Islam

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)